The A-Eye Unit at the University of Wisconsin—Madison began with a spark of curiosity and Dr. Amitha Domalpally’s lifelong passion for technology. “I’ve always loved gadgets and gizmos,” she recalls, “anything that would enable me to see the world differently.”

That curiosity found fertile ground in 2017 at the Wisconsin Reading Center (WRC)— a retinal image reading lab within the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences (DOVS). Dr. Domalpally, an associate professor of ophthalmology and research director at the WRC, collaborated with Dr. Michael Abramoff at the University of Iowa to train some of the earliest artificial intelligence (AI) models in ophthalmology. The initiative put the University of Wisconsin on the forefront of AI technology.

“AI wasn’t a buzzword yet,” Dr. Domalpally said. “It hadn’t even been discussed in medical imaging. It was purely experimental—and a lot of fun.”

In 2018, the FDA approved the first trial of AI in ophthalmology— the very first in all of medical sciences. After completing her PhD in 2019, Dr. Domalpally made the case to establish a dedicated AI unit within DOVS. Two years later, the A-EYE Research unit was officially launched, hiring its first AI scientist and acquiring a graphics processing unit.

“Our first effort wasn’t glamorous,” Dr. Domalpally recalls. “It was simply to prove that an AI model could work in ophthalmology.” That initial model identified the part of the retina from which an image originated—small but groundbreaking proof of concept.

From there, the unit grew—curating images, training models, and testing them. Today, the A‑Eye Unit has expanded to a staff of eight, with three AI models already in production and more in the pipeline.

“These models are not meant to replace human graders, but to support them. AI does the preliminary work, enabling graders to focus on the higher-level skills that require human input, including reviewing what AI does.”

Training AI in ophthalmology is uniquely challenging, given the wide variation in disease, image quality, and patient co-morbidities. Still, the unit set its sights on models achieving high accuracy.

One of the unit’s most impactful projects came in 2022, when an AI model was developed to measure geographic atrophy (GA) in patients with age‑related macular degeneration (AMD). Clinical trials often require GA lesions to be within a specific size range, but clinics had no reliable way to measure them. As a result, nearly half of patients underwent unnecessary testing only to be disqualified.

“Our model enabled clinics to prescreen patients,” Dr. Domalpally said. “If the AI model detects the patient likely meets the criteria, then the patient would undergo further testing. It’s been very successful. We realized at the end of study, that when AI hadn’t been used, the screen fail rate was as high as 40%. But with the use of AI, ophthalmologists were able to bring it down to 15%.”

Their AI model is now cloud‑based, allowing secure, password‑protected access to heath care providers worldwide—saving patients, clinics, and sponsors significant time and resources.

Another groundbreaking WRC contribution is towards Bridge2AI, a public database holding the largest collection of ophthalmic images in patients with diabetes—nearly 4,000 patients strong. The catch? They’re unlabeled and cannot be used for AI development. WRC is tackling that challenge head-on, creating a resource primed for AI breakthroughs.

With new servers and powerful processors, the team is testing diffusion models that generate synthetic images to overcome barriers in medical imaging. Early results are promising: AI may soon predict angiogram outcomes from simple color photos, sparing patients invasive and costly procedures, while enabling earlier disease detection.

Dr. Domalpally also hopes AI will one day assist in the diagnosis of multiple eye diseases at once. Currently, the FDA has approved three algorithms in ophthalmology—but all are for diabetic retinopathy. “I started to wonder,” she said, “why couldn’t we build a model that detects diabetic retinopathy, AMD, and glaucoma together?”

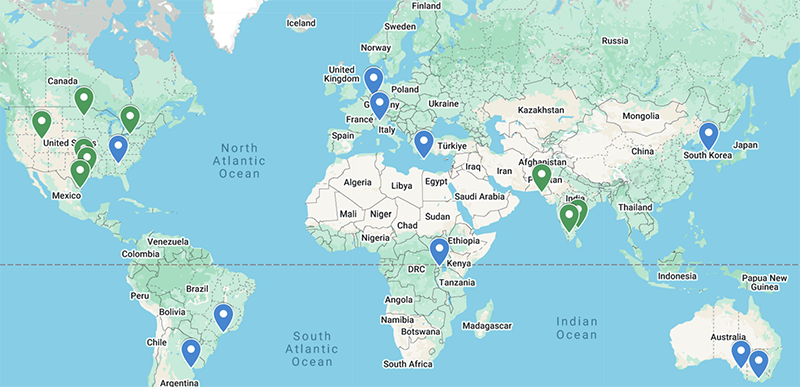

The ABID study, sponsored by UW, is a major step toward that end. With 1,000 patients enrolled across 25 clinics worldwide, it is assembling one of the largest, most diverse AMD datasets ever assembled. This effort brings the field closer to AI models capable of diagnosing multiple diseases with accuracy and equity.

“The WRC and A-EYE unit are proud to partner in projects like these,” Dr. Domalpally said. “Reliable AI tools can expand access to eye care, improve early detection, and ultimately help prevent vision loss worldwide.”