In the operating room, Ruth Manning was a little nervous. Two years of eye trouble had led her here. Yasmin Bradfield, MD, pediatric ophthalmology and adult strabismus specialist, completed the last tasks before beginning surgery.

“You know, Ruth,” Dr. Bradfield said calmly, “this is not an exact science. There is an art to this.”

It was a wise thing to say to this particular patient.

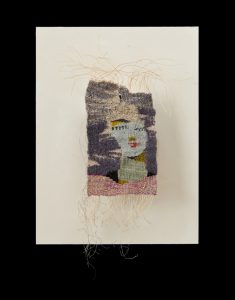

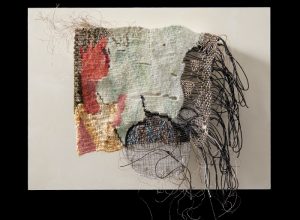

Manning is an artist. Her mother’s sewing skills influenced her at an early age, along with growing up in the 60s. Manning acquired her first loom when she was 16. Fiber-related art has remained a constant throughout her life.

A native of Rochester, New York, Manning majored in photography at the Rochester Institute of Technology. She spent the next 30 years in Rochester, raising children and creating tapestries at her studio at Anderson Alley, an artists’ collective, from 1993 to 2003. In her 50s, Manning moved to Maryland and chose a different way to share her art with the world as an elementary art teacher. She realized that she needed a broader art knowledge, “at least enough to impress a fifth grader,” she quipped, and began to get more involved in drawing and sketching. As Manning worked on boosting her new skills, sketching became a daily practice.

In 2010, Manning decided to relocate to Madison, Wisconsin, to be closer to her son, who was working for Epic Systems Corporation at the time. He’s since relocated to the Twin Cities in Minnesota, but Manning felt that her new home shared similarities with Rochester and decided to stay. She has been a substitute teacher in the area since she arrived.

Teaching, though, has its challenges, and Manning began to entertain ideas of how to she could feed her hungry art side. Eventually, she came up with an idea. When she arrived home each day, she drew the first thing that came into her mind. The project turned into a three-year commitment, which is just now wrapping up.

Back in February of 2018, Manning woke up one morning for work. Something didn’t feel right in her eye. She thought it must be pink eye, but it didn’t go away. Manning decided she needed an eye exam, and her optometrist referred her to Marilyn Kay, MD, a neuro-ophthalmologist at UW Health.

Manning had been suffering from a low thyroid issue for 15 years. No one along the way had warned her to watch out for any symptoms in her eyes. When Dr. Kay walked into the room, she had a pretty good idea of a diagnosis, as Manning’s eye were bulging, a telltale sign of thyroid eye disease. Further testing confirmed it.

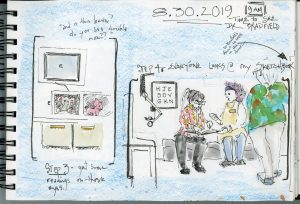

Manning received intravenous steroid injections every Thursday for the next 10 weeks to reduce the inflammation. She had a routine at the appointments. She brought along a favorite shawl, her sketchbook and her drawing tools. She drew her hand with a needle in it. She drew nurses and the funny things they said. Manning easily recalls her second injection. That was the day she sketched a nurse named Lolly saying, “I was going to be an ASL interpreter, but it got too messy.”

Manning was plunged into her first intensive experience with a medical system. As the fear and confusion crept in, Manning’s artistic way of navigating through the world kicked in.

“I went through the whole medical process. I had to deal with it. What does it mean, how can I draw this out. When I didn’t understand it, I did a lot of drawings. It was a very complex thing. I could have asked questions, but I wasn’t sure what to ask. And then I was too afraid to look it up. Then one day, I went to the library. And I drew a sketch of myself at the library that was, ‘Today I’m a big girl, I’m going to look up strabismus.’”

Strabismus. It was the next obstacle to address. After the second injection, Manning’s eyes calmed down. But the calm exposed the damage that the disease had caused. Her eye muscles were scarred from the inflammation. Manning had little to no upward movement in her eyes and had to move her head to look around. She was functioning within a four-foot diameter. She could still read and create art. But once she looked up, it was too distressing. The irritation, vertigo and pain made her world close in around her.

Dr. Kay referred Manning to Dr. Bradfield. In January of 2019, Manning met with Dr. Bradfield and strabismus surgery was scheduled to correct the eye muscles. “You’re stuck with this [strabismus],” Manning said, “unless you find magical Dr. Bradfield.”

Dr. Bradfield fixed the biggest problem, the twisting and vertical double vision, but Manning still has a residual small amount of horizontal double vision so she wears glasses with a temporary prism. Dr. Bradfield encouraged her to use temporary prisms for now, until her eyes settle where they want to be and they can chart a more permanent prism prescription. “That’s the creativity part,” Manning notes. “All my life I’ve known various people, artists, scientists. One of the big talking points with those crowds, when they get together, is there is so much similarity between the way the two of us work. Art and science.” Manning is now challenging herself to figure out how to weave a prism into her latest self-portrait, no easy task.

She’s back at school, teaching kids two days a week. The kids like the prism in her glasses. If the light catches it just right, they can see rainbows in them. “‘What’s wrong with your eye?’, the kids say. And I say, ‘This is magic. Let me tell you about it.’”

To learn more about the art of Ruth Manning, visit www.ruthmanningtapestry.com